What is Champagne?

Oct 20, 2014, Updated Dec 16, 2024

This post may contain affiliate links. Read more at our disclosure policy.

What exactly is Champagne? What makes it different from other sparkling wines from the world?

Table of Contents

- “Bubbles,” “Sparkling Wine,” “Champagne” — What’s the difference?

- Champagne is a Place

- How is Champagne made?

- Permitted Grapes in Champagne

- The Traditional Method, or Méthode Champenoise

- Why is Champagne so expensive?

- Styles of Champagne

- Sweetness Levels in Champagne

- Sparkling Wine outside of Champagne

- Important Tidbits about Champagne

- Recommendations for Champagne

- How to safely open a bottle of Sparkling Wine

- Recipes to pair with Champagne

- More Resources on Champagne and Sparkling Wine

For several summers I was hired by the Comité Champagne (the U.S. Champagne Bureau) to teach a series of Champagne classes in Portland to spread the love for this magical sparkling drink and I learned something eye opening.

I was astonished to discover how few people actually understand that Champagne is actually a place. Many students associated the word “Champagne” with anything bubbly. I suppose living in my little wine bubble (pun intended) I assumed everyone knows the difference between “Champagne” and “sparkling wine,” but I was wrong.

So in honor of my most favorite beverage I decided to dust off and old primer I wrote years ago, in hopes it may lead you to a better understanding of such an important drink.

“Bubbles,” “Sparkling Wine,” “Champagne” — What’s the difference?

I often use the word “bubbles” synonymously with “sparkling wine” — basically wine that sparkles, has fizz or even a slight effervescence. The first thing to know about “Champagne” is that it is only true Champagne when it comes from the Champagne region of France. Sparkling wine made outside of this region is just that – sparkling wine, or if you’re like me, you can refer to it as simply “bubbles.” It is very important to know this key bit of information.

What is so special about Champagne?

The process of making Champagne within this region is complex, time consuming, highly regulated, and dependent on factors that can only be achieved within this very region in order to create a very high quality product.

Don’t get me wrong, there are some absolutely lovely sparkling wines being made in a similar way outside of Champagne, but they are NOT Champagne.

Let’s get started with the basics.

Champagne is a Place

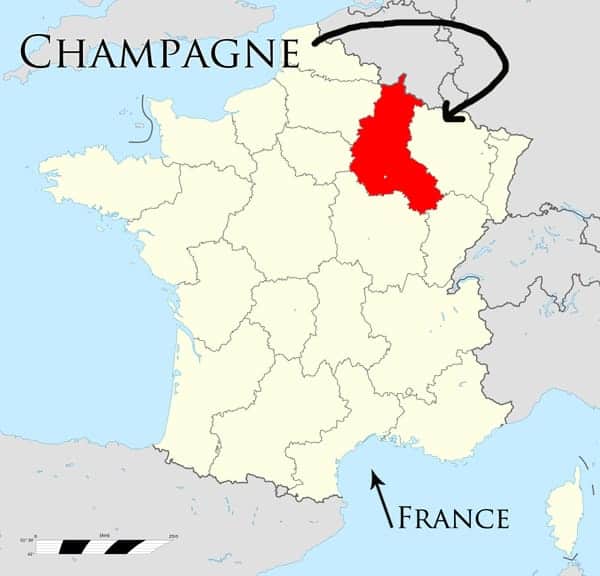

Champagne is a region located approximately 90 miles northeast of Paris, France. While vines have been producing wine in this region since the Roman era, it is only in the past couple hundred years that they began producing it in the method associated with it today (i.e. bubbly).

Within this region chalk and limestone soils dominate which result in wines high in acidity (a KEY component to making good sparkling wine). Its northerly location, about as north as grapes can ripen, is what allows for higher acidity and lower alcohol levels (also very important for quality sparkling wine).

Without getting too technical for this overview, it is basically the soils, vineyard conditions, and regulated method of production (described next), that all affect the overall product.

How is Champagne made?

This information is key to the quality of the end product. The regulations for making Champagne are incredibly strict, unlike here in the U.S. where methods of sparkling wine are not regulated (although the highest quality sparkling wines here in the U.S. do use the method described below). They must follow these steps:

Permitted Grapes in Champagne

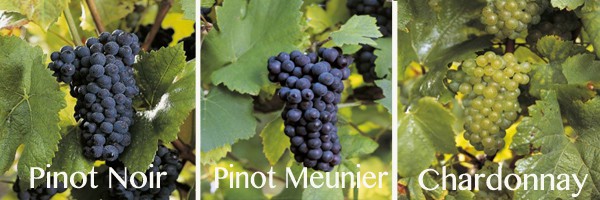

There are three primary grapes used in Champagne production – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier. While there are a few other grapes permitted in the region, they account for a fraction of the total plantings.

The Traditional Method, or Méthode Champenoise

- Primary Fermentation: The grapes go through a traditional harvest much like any other wine and undergo Primary (First) Fermentation: This usually results in a wine that is between 10.5 – 11% alcohol and very high acidity (definitely not ready to drink yet!). At this point the wine is a still wine (no bubbles yet).

- Assemblage: This is where blending occurs. Wines from different grape varieties, vineyards and vintages are all blended together. This is to create a consistent style year after year so that you, as a consumer, will know that the wine you love right now will likely maintain a consistent flavor year after year. Unlike many other styles of wine that can taste vastly different vintage after vintage, the goal of many Champagne producers is to create a consistent “house style,” reflected year after year. (This is not always the case, but it is in most cases.) Once the wines are blended, they are put into a bottle.

- Liqueur de Tirage: This is where a measured quantity of cane sugar & yeast cultures are added to the mix to stimulate the second alcoholic fermentation. This takes place in a long necked, dark green bottle with a crown cap like a glass beer bottle.

- Second Fermentation: This occurs slowly within the bottles. This process can last anywhere from 1-3 weeks. Then the bottles are laid sideways to rest, mature, and age on their lees. The aging on the lees are what aids in the “toasty” “doughy” “bread” like characteristics. French law requires 15 months of aging after the wine is bottled for non-vintage Champagne and at least 36 months for a vintage dated wine. This is time consuming! After the allotted time lots of yeast cells have settled to the bottom. They now need to be removed.

- Remuage or Riddling: This is the process that requires twisting of the bottles to move the sediment towards the bottle cap (to get rid of it). This can be done by hand or machine and can take up to a week (mechanically) or two months if done by hand. This point is to get all the sediment to the tip of the bottle (the bottles are now stacked upside down) in preparation for the next step.

- Disgorging or Dégorgement: This is the process of removing that gob of yeast residue that has now settled in the neck of the bottle. The neck of the bottle basically goes through a process of flash freezing. The lees are now frozen solid and can be carefully removed. The bottle cap is then popped open, and the CO2 pushes the frozen lees right out of the bottle. Boom!

- Addition of the Liqueur d’Expedition: The bottle is now topped up with small measured portion of additional Champagne in order to replace the quantity that was lost during disgorging. This “dosage” also contains a level of sugar that will determine the desired style of sweetness (see below under “sweetness levels of sparkling wine).

Would you like to save this?

- Re-corking: The bottle is now corked with a proper Champagne cork and sealed with wire cage (for protection), and is almost ready for sale (after a few months of additional resting time).

The process is time consuming, requires specialized equipment, and is very expensive.

Why is Champagne so expensive?

Many people ask me why Champagne can be so expensive, and my answer is that it is a very meticulous and expensive process to begin with. For those who make Champagne it can be a labor of love, but one so very worth it when you taste the end product!

Styles of Champagne

Champagne comes in a variety of styles and levels of sweetness. It is important to understand this when you are shopping for a bottle, so you get what you want.

- Blanc de Blanc: literally means “white from white,” white wine made from white (Chardonnay) grapes, and usually lighter in style than the following types.

- Blanc de Noir: translates to “white from black,” meaning white wine made from black grapes (Pinot Noir and/or Pinot Meunier).

- Rosé: most often made by blending red wine and white wine together prior to bottling.

- Non-Vintage (NV): meaning that the wines are a blend of different vintages of wines. Champagne producers blend multiple vintages together in order to achieve a consistent “house style.” This creates consistency, so that you the consumer can expect similar tasting product year after year.

- Vintage Champagne: produced only in the most exceptional years, and 100% of the grapes used must come from the vintage stated on the bottle. Less than 10% of Champagne produced each year is vintage Champagne. You will see the year of harvest labeled on the bottle.

Sweetness Levels in Champagne

This refers back to that small dose of sugar (dosage) that is added to the wine prior to determining what style of wine (level of sweetness) it will be. Understanding these terms will come in handy if you are particular about a wines level of sweetness (like I am!)

- Brut Naturelle/Non Dosage: bone dry, usually no sugar is added

- Extra Brut: very dry, less than 1%

- Brut: very dry to fairly dry (this is also the most common style you’ll see)

- Extra Sec or Extra Dry: dry to medium dry (around 3% sugar)

- Sec: medium dry, or some call it medium sweet, whatever you call it it’s right there in the middle of the scale

- Demi-Sec: we’re getting sweet here people

- Doux: Boo yah…..think dessert, because that’s the level of sweetness we’re talking about here. Like pucker up and hand me a cookie sweet.

Sparkling Wine outside of Champagne

One of the most vital things to note is that Champagne is ONLY “Champagne” when it comes from the Champagne region of France. Wines made in this method, produced outside of Champagne, are just sparkling wine. They can be labeled under other names. To understand more about sparkling wines produced in other regions, please check out this post on the very subject. It discusses other styles of bubbly, like Crémant, Cava, Prosecco, and sparkling wines produced here in the US and elsewhere.

Important Tidbits about Champagne

- True Champagne ONLY comes from the Champagne region of France (that bottle labeled Korbel California Champagne is NOT Champagne, but instead just “sparkling wine”).

- The primary grapes used in Champagne production are Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier.

- Most Champagne is a blend of grapes, vintages, and vineyards. The key is to create a consistent tasting wine (“house style”) year after year with the exception of “vintage specific Champagne.”

- The traditional method creates sparkling wines of the very highest quality. It is very time consuming requiring specific steps to ensure such quality.

- Most importantly, Champagne is the greatest beverage on the planet! Don’t even try to debate me on this point because I WILL WIN!

Recommendations for Champagne

All of these wines were examples I used in the classes I taught, with the exception of the Pierre Peters (that just happens to be my personal fav). They reflect good examples of their respective “styles.”

Non-Vintage House Style

- Piper-Heidsieck NV Brut ($40)

- Etienne Chere Brut Tradition NV ($47)

- Ployez-Jacquemart Extra Brut Passion NV ($48)

Zero Dosage

- Philipponnat Royale Réserve Non Dosé ($42)

Blanc de Blanc

- Gaston Chiquet Grand Cru Blanc de Blancs d’Aÿ ($60)

- Dosnon & Lepage Recolte Blanche Blanc de Blancs Brut NV ($53)

- Pierre Peters “Cuvée de Réserve” Brut Blanc de Blancs Champagne ($58)

Rosé

- Lallier Rosé Premier Cru Brut NV ($50)

- Dosnon & Lepage Récolte Rosé ($58)

Don’t want to pay more than $40 for a bottle? I tested out the Kirkland Champagne a few weeks ago and it was worth its $20 price tag (no joke!). If you haven’t had a real Champagne and want to test the waters without breaking the bank I recommend you head over to your nearest Costco and fork over a Jackson. It’s not as complex or interesting as the wines listed above, but it is true Champagne.

How to safely open a bottle of Sparkling Wine

It may seem self explanatory, but it’s worth note. There is a lot of pressure inside that bottle! So take the proper precautions and open it safely with these important steps.

Recipes to pair with Champagne

- Grilled Oysters

- Grilled Lobster Tails

- Smoked Whole Chicken

- Smoked Salmon Dip

- Smoked Bone Marrow, from our cookbook, Fire + Wine

More Resources on Champagne and Sparkling Wine

- Sparkling Wines outside of Champagne — What to know

- Champagne vs. Prosecco

- Sparkling Wines of Italy

- Sparkling Wines to Buy

*Photos of aerial view of Champagne, grape clusters, and blending wine were used with permission from the Comité Champagne. Map adapted from Wikimedia. Riddling rack was my own photo.

Philipponnat Royale Réserve Non Dosé is one of my favorite!